Zombie Viruses: Fascinating and a Little Frightening

Wednesday, August 23, 2023 at 11:34AM

Wednesday, August 23, 2023 at 11:34AM “‘Entry events’ do happen, very rarely, and they can shape human evolution,” says Liston. “Major examples would be smallpox (a virus) and tuberculosis (a bacteria), which strongly influenced human evolution when they entered our species, selecting for the type of immune system that was able to fight them and killing off individuals with the ‘wrong’ type of immune system.”

“The most important take-home message is that climate change is going to create unexpected problems,” says Liston. “It isn’t simply changes to weather, climate events, and sea levels rising. A whole cascade of secondary problems will be generated. New infections, some of which could go pandemic, are almost certainly going to happen because of climate change.”

The Tissue Treg project

Wednesday, August 23, 2023 at 11:25AM

Wednesday, August 23, 2023 at 11:25AM Biggest paper yet from the lab now a preprint on BioRxiv. A massive open science resource on tissue Tregs, and what makes Tregs tick in the tissues.

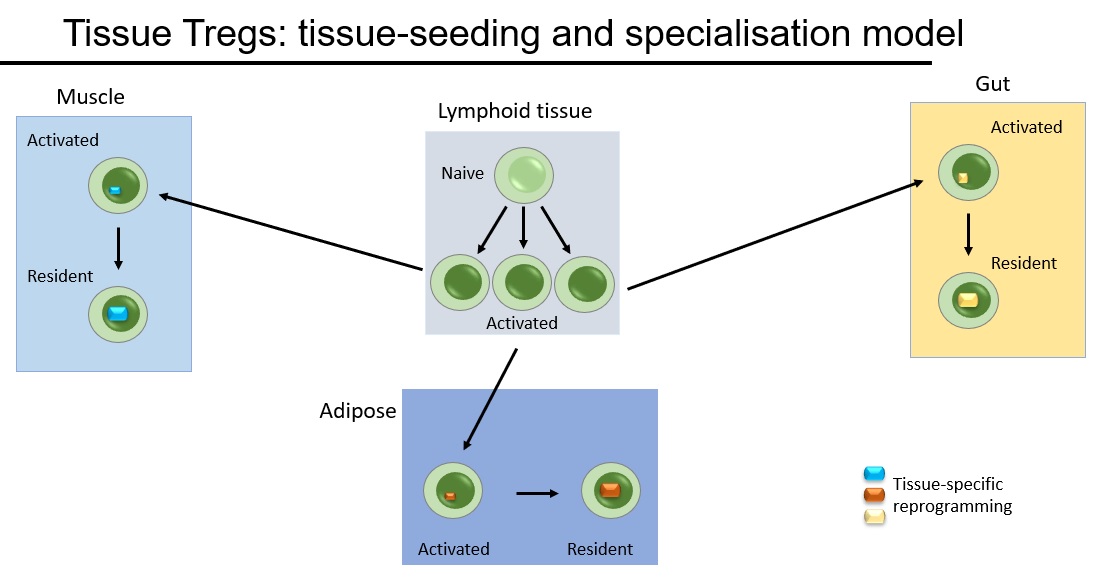

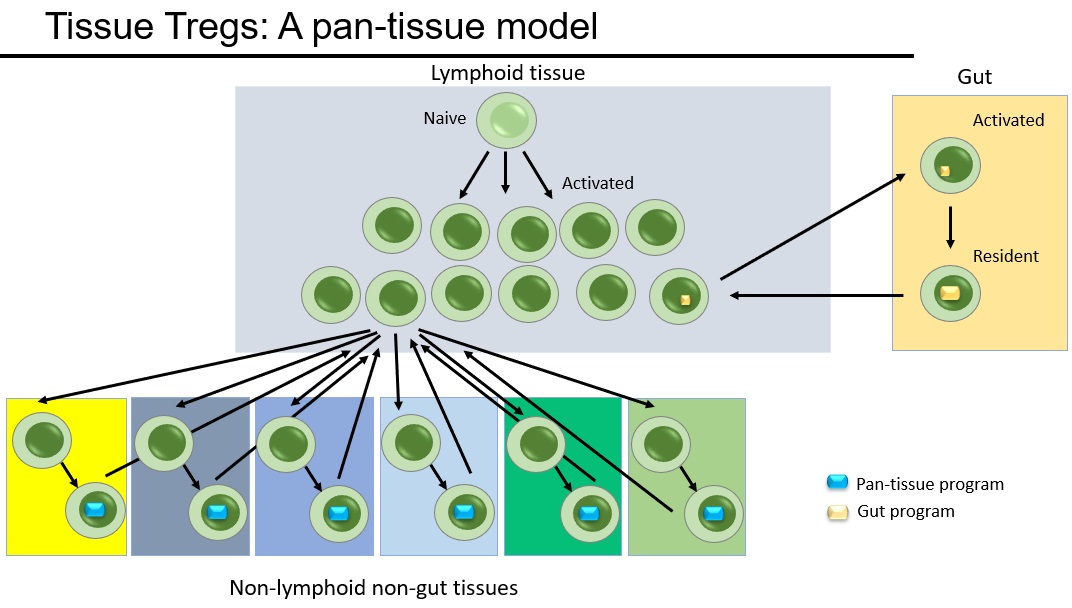

This project started back when we thought that tissue Tregs formed by seeding tissues and differentiating into unique terminal cells. We had examples of fat Tregs and muscle Tregs becoming unique permanent residents, and wanted to look at Tregs across the tissues.

We undertook a massive project to look at Tregs across 48 different tissues. At first glance, tissue Tregs looked special. Take a tissue and compare it against lymphoid/blood Tregs and the differences are huge. But the more tissues you add, the more they look the same. The only three distinct phenotypes were gut, lymphoid and bulk non-lymphoid. (Try our interactive web-browser resource). They have the same phenotypes, they use the same genetic triggers to differentiate and they only stay in the tissues for around 3 weeks. In short, the "seeding & specialisation" model doesn't fit the data.

Instead we came up with the "pan tissue" model, where tissue Tregs slowly percolate between different tissues. We've spent years testing this model in every possible way. We used the TCR as genetic barcodes, showing that the same Treg #clones are found in different tissues. We used ProCode technology to make #retrogenics for the tissue Treg TCRs, formally demonstrating that they impart a multi-tissue Treg fate. We extracted cells from tissues and reintroduced them, showing that they are tissue-agnostic on rehoming. By every test, the "pan-tissue" model holds strong.

What is amazing is that tissue Tregs have so many key functions in tissue repair and homeostasis, and now we find that it is the same cells that are able to restore the balance across all of these different tissues. Tissue Tregs are global homeostatic police. They are regulatory cells with a pan-tissue beat. A truly amazing cell type.

Could only have happened due to an amazing team - lead by Oliver, Burton, Orian Bricard and James Dooley.

Liston lab,

Liston lab,  immunology

immunology A New Hope for IPEX patients

Tuesday, May 9, 2023 at 10:51PM

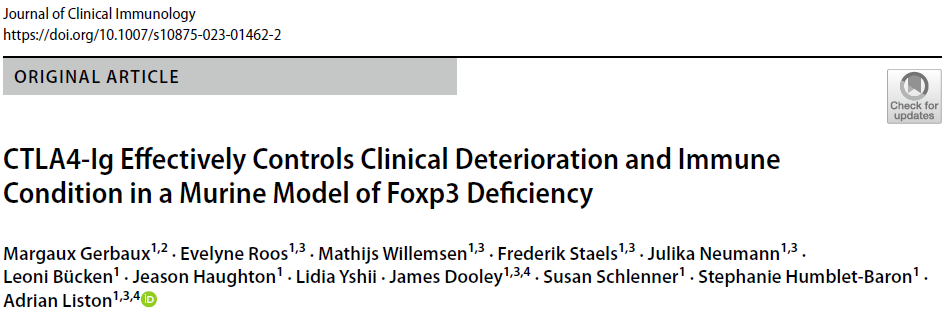

Tuesday, May 9, 2023 at 10:51PM A new paper from our lab suggests a novel approach to treating IPEX patients. IPEX is a rare severe primary immunodeficiency, caused by a genetic deficiency in the gene FOXP3, which results in a lack of anti-inflammatory regulatory T cells.

IPEX is usually fatal in childhood if left untreated. The only cure is a haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, however patients are often so sick from autoimmunity that they are in poor condition to receive a transplant. The patients are put on symptomatic support (hormonal and nutritional supplements to compensate for the damaged organs) and immunosuppressive drugs to reduce further damage. These immunosuppressive drugs are typically combinations of cyclosporine A, tacrolimus, rapamycin and corticosteroids, although recently biologics such as orthoclone have been suggested. Unfortunately the patient cohort has been too small and heterogeneous to allow a proper clinical trials as to which immunosuppression regimen works best.

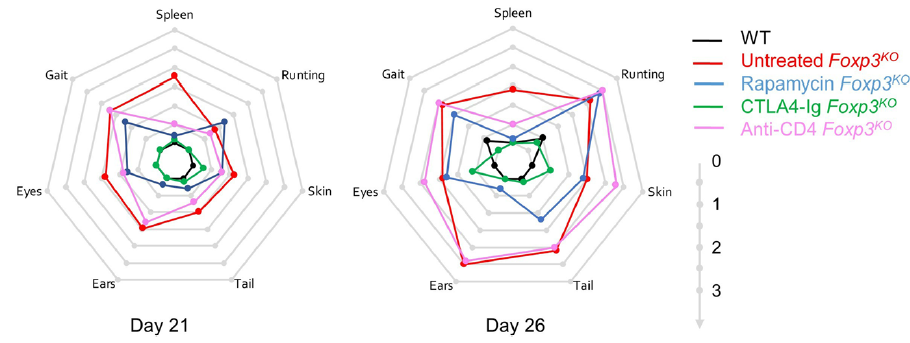

We sought to answer this by turning to the mouse model - also with a genetic deficiency in Foxp3 and a lack of regulatory T cells. We developed a comprehensive pathology scoring system for the model that takes into account the multiple different autoimmune symptoms, and then tested in a side-by-side comparison rapamycin (the most common standard treatment), anti-CD4 antibody (analgous to orthoclone in its proposed approach) and CTLA4-Ig (based on our prior work on CTLA4-Ig compensating well for Treg-deficiency).

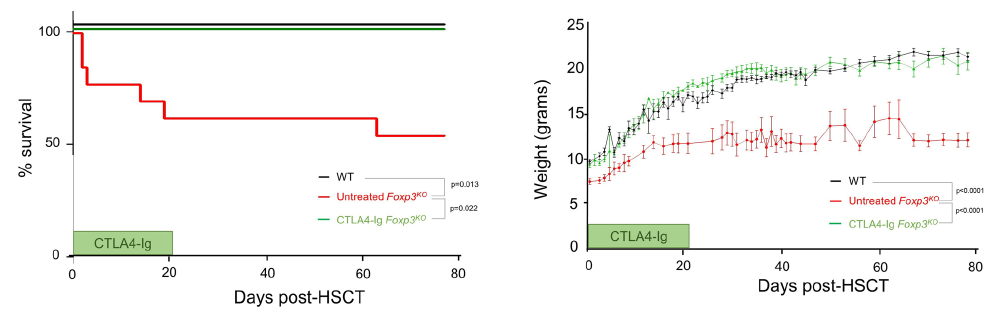

The results were striking. As seen in patients, rapamcyin cleared up some of the skin pathology, but otherwise it had little impact on the course of pathology in the mice. Anti-CD4 antibody prevented many of the immunology symptoms, but again, didn't actually improve the aggregate health outcomes of the mice. CTLA4-Ig, by contrast, improved essentially every parameter - the mice started gaining weight like normal, improved their serology, skin pathology and organ histology - and had greatly improved life-spans. Most importantly, the overall condition of the CTLA4-Ig-treated mice improved to such an extent that they were capable of supporting curative bone-marrow transplants: survival improved from 50% to 100% in mice given CTLA4-Ig prior to transplantation.

There are caveats to every disease model, however we believe this is sufficient evidence to strongly consider a clinical trial of CTLA4-Ig (abatacept) in IPEX patients. The genetic and cellular defects are entirely conserved between mouse and human in this case, and the drug is in widespread use in patients for other autoimmune conditions (such as arthritis). We know that there are IPEX patients who respond poorly to the current standard treatments and need to improve their condition before receiving a bone-marrow transplant. CTLA4-Ig treatment could be the bridge that these patients need to the curative transplantation!

Thanks to the Jeffrey Modell Foundation for sponsoring this study, which was done in collaboration with lab alumni Prof Stephanie Humblet-Baron at the University of Leuven in Belgium. Check out the full paper at the Journal of Clinical Immunology!

Liston lab,

Liston lab,  Medicine,

Medicine,  immunology

immunology The key to healthy aging brains

Tuesday, May 9, 2023 at 6:59PM

Tuesday, May 9, 2023 at 6:59PM As people age, they often experience problems with their memory and cognitive abilities. This happens in part because their brains become mildly inflamed. But there may be a solution: a small group of special T cells, called regulatory T cells, could help reduce this inflammation in aging brains. Administering a protein called interleukin-2 (IL2) can help these special T cells grow and prevent inflammation. Now, researchers at VIB, KU Leuven, Babraham Institute, and i3S have tested this approach in mice and found that it can prevent neurological decline. Their findings, published in EMBO Molecular Medicine suggest that targeting the immune system might keep people’s brains healthy as they age.

Emanuela Pasciuto, co-first author of the study: “Our goal was to see whether we could slow down the aging process of the brain by changing its immune system through the delivery of IL2. We know that inflammation plays a significant role in various aging processes, and IL2 could help us tilt the balance back in our favor.”

Inflammation in the aging brain

Aging is a degenerative process that affects the whole body, including the brain. As we age, our brains may experience cognitive decline, affecting our memory and ability to think clearly. Increasing evidence suggests that inflammation in the brain, called “inflammaging,” can worsen this decline. Inflammaging is caused by immune cells entering the brain as we age. This inflammation can activate microglia, the resident immune cells in the brain, and induce neuroinflammation, leading to cognitive decline and dementia.

Aging is a degenerative process that affects the whole body, including the brain. As we age, our brains may experience cognitive decline, affecting our memory and ability to think clearly. Increasing evidence suggests that inflammation in the brain, called “inflammaging,” can worsen this decline. Inflammaging is caused by immune cells entering the brain as we age. This inflammation can activate microglia, the resident immune cells in the brain, and induce neuroinflammation, leading to cognitive decline and dementia.

However, researchers have found a way to reduce inflammation in the brain by targeting a small group of special immune cells in the brain called regulatory T cells. Previously, the team of Adrian Liston (VIB-KU Leuven, Babraham Institute) and Matthew Holt (VIB-KU Leuven, i3S Porto) showed that administering a protein called Interleukin-2 (IL2), which helps regulate the immune response, increased the number of regulatory T cells in the brain. This treatment has been successful in mouse models of traumatic brain injury and neuroinflammation.

Now, the researchers want to see if delivering IL2 directly to the brain can help reduce age-induced inflammation and cognitive decline.

Gene therapy improves brain aging

In their latest study, the team discovered that delivering IL2 to the brain improved brain function in aging mice. The research showed that the treatment restored cognitive performance in spatial memory tests, allowing older mice to form new memories almost as well as young mice. The mice given IL2 treatment were better at remembering visual cues than those that did not receive the treatment. Additionally, some of the changes in cellular aging in the brain were reversed, especially among several types of glial cells, which are critical to support overall brain function and health.

Pierre Lemaitre, co-first author of the study: “Our approach was to harness the body’s own system to regulate inflammation and to boost it precisely where it was needed.”

IL2 was delivered to the brain using a gene therapy vector, which is a tool that provides genetic material to specific cells. The additional dose of IL2 allowed the regulatory T cells to survive and create an anti-inflammatory environment. Matthew Holt and Lidia Yshii, co-senior authors of the study: “This reinforces our belief that viral vector-based systems are the way forward for the delivery of therapeutics to combat chronic neurodegenerative diseases and preventing cognitive decline in aging populations.”

Adrian Liston, senior author of the study: “The most important part of this study is the high potential for translation into patients. Inflammation is a process that is conserved in both mice and humans, and regulatory T cells can respond to IL2 in both species. However, there are still regulatory hurdles to clear, and it’s crucial to ensure safety before testing it in patients. Nonetheless, we see a clear path to conducting clinical trials.”

The laboratory is working through spin-off company Aila Biotech to drive entry of this therapeutic into clinical trials. Read the full study here.

Liston lab,

Liston lab,  Medicine,

Medicine,  immunology,

immunology,  neuroscience

neuroscience Happy International Women's Day

Wednesday, March 8, 2023 at 2:24PM

Wednesday, March 8, 2023 at 2:24PM

From Magda Ali, Ntombizodwa Makuyana and Amy Dashwood, PhD students in our lab.

Liston lab,

Liston lab,  women in science

women in science Innovative treatment prevents development of diabetes

Thursday, December 8, 2022 at 1:01AM

Thursday, December 8, 2022 at 1:01AM Key points:

- Researchers from the Babraham Institute have been able to prevent the development of diabetes in mice.

- Their study prevented the death of insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas, blocking the development of diabetes

- The treatment used a modified virus to manipulate a key molecular pathway in pancreatic cells, which controls the decision of stressed cells on whether to live or die.

- The team hope that their findings will translate into clinical treatment for both types of diabetes.

Researchers from the Liston lab have recently published a preventative therapeutic for diabetes in mice. Their team have been able to prevent diabetes in mice by manipulating signalling pathways in pancreatic cells and preventing stress-induced cell death. The treatment targets a pathway common to both major types of diabetes and therefore could have huge therapeutic potential once translated into a clinical treatment.

For over 35 years there have been failed attempts to prevent type 1 diabetes development. Previous approaches have sought to target the autoimmune nature of the disease, but Dr Adrian Liston, senior Group Leader in the Immunology research programme, wanted to investigate if there was more causing the deterioration in later stages than just the immune response.

The Liston lab sought to understand the role of cell death in the development of diabetes and therefore approached this problem by identifying the pathways that decide whether stressed insulin-producing cells of the pancreas live or die, and therefore determine the development of disease.

Their hope was to find a way to stop this stress-related death, preventing the decline into diabetes without the need to focus solely on the immune system. First, the researchers had to know which pathways would influence the decision of life or death for the beta cell. In previous research, they were able to identify Manf as a protective protein against stress induced cell death, and Glis3 which sets the level of Manf in the cells. While type 1 and 2 diabetes in patients usually have different causes and different genetics, the GLIS3-MANF pathway is a common feature for both conditions and therefore an attractive target for treatments.

In order to manipulate the Manf pathway, the researchers developed a gene delivery system based on a modified virus known as an AAV gene delivery system. The AAV targets beta cells, and allows these cells to make more of the pro-survival protein Manf, tipping the life-or-death decision in favour of continued survival. To test their treatment, the researchers treated mice susceptible to spontaneous development of autoimmune diabetes. Treating pre-diabetic mice resulted in a lower rate of diabetes development from 58% to 18%. This research in mice is a key first step in the development of treatments for human patients.

“A key advantage of targeting this particular pathway is the high likelihood that it works in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes”, explains Dr Adrian Liston. “In type 2 diabetes, while the initial problem is insulin-insensitivity in the liver, most of the severe complications arise in patients where the beta cells of the pancreas have been chronically stressed by the need to make more and more insulin. By treating early type 2 diabetes with this approach, or a similar one, we have the potential to block progression to the major adverse events in late-stage type 2 diabetes.”

Liston lab,

Liston lab,  diabetes

diabetes